|

EXCLUSIVE: After a spectacular run that witnessed Pantera emerge from their native Texas in the late 1980s, to becoming one of the biggest metal bands on the planet by the late 1990s, the foursome parted ways – unexpectedly – for the final time in 2001. That wasn’t before leaving one final album, a set that bassist Rex Brown looks back on as; “very focused, and cohesive”. Of course getting there, there is a huge story to tell; from the earliest days of ‘Metal Magic’, to a Billboard No.1 album, and beyond. We caught up with Rex for an extended chat about the ‘Reinventing the Steel 20th Anniversary Edition’, and Pantera’s rise, fall, and legacy. Hellbound; Eamon O’Neill.

Hi Rex, how are you today?

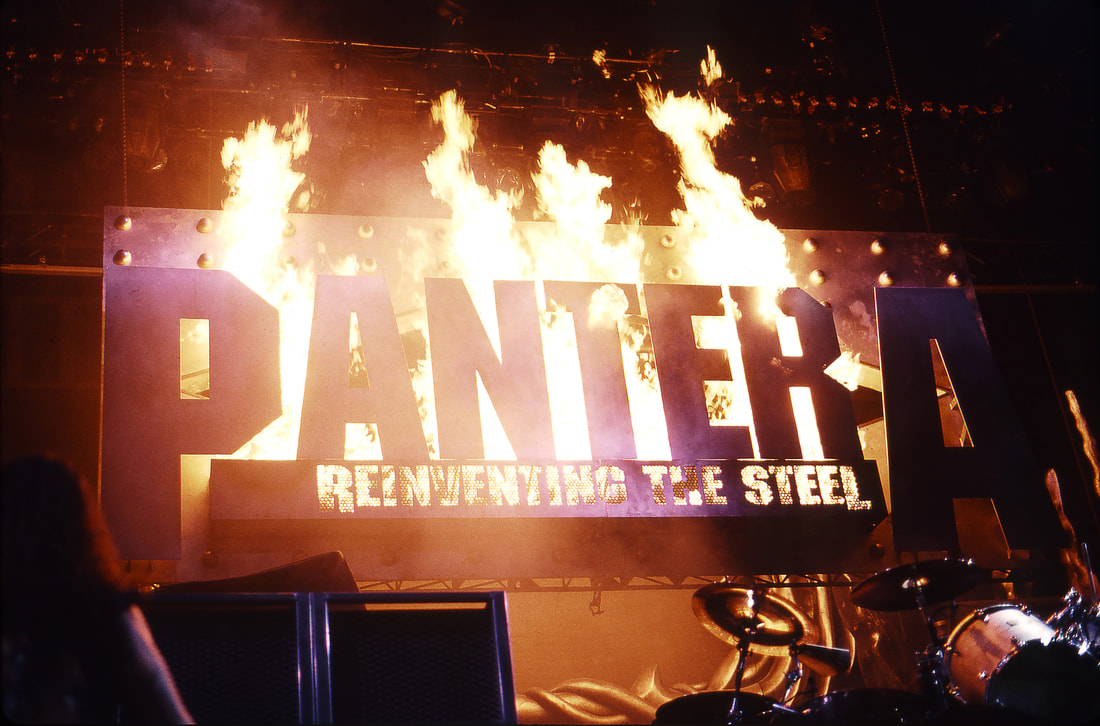

I’m good. I’m watching the snow melt here at the ranch in New Mexico, and it's all good man, all good! We’re here to talk about the reissue of Pantera’s final album ‘Reinventing the Steel’, which was originally released just over two decades ago; does it seem like it was that long ago? Yeah, we played our last note about nineteen years ago, and that was the end of the touring cycle. We had one more run to do in Europe [‘Tattoo the Planet’, co-headlining tour with Slayer] , and I was thinking of this today; it crossed my mind that when we were recording this record, we were very, very focused and it was all back to normal. Phil [Anselmo, vocals] was coherent, and we pursued this thing from a different standpoint where we really needed to go back and take a look at each of the records that we’d done. So it was a very defined process, creating the album? It started a riff tape, and the stuff the Dime [guitarist, Dimebag Darrell] had. We just decided; everybody write down their five favourite songs that we had done, ever, and so you had four different lists. I think the one thing that Phil wanted to get across was he wanted to be more anthemic. ‘Walk’ was starting to be played at football games to 80,000 people over the P.A., which is insane now because every time you go to a sporting event you’re going to hear a Pantera song - it’s nuts! This legacy has followed us around. What was the recording like? When we went into the studio, Philip had basically moved into Dime’s spare bedroom at his big house in South Arlington, and we got to work. We would write three or four or five songs, and then Philip would go home for about a month and come back, and that’s the way we always liked to do stuff. On the first few records we would just get in just knock ‘em out, you know? And then we started taking breaks in between because it’s just good to keep fresh. Also, we were just on the road all the time, and around each other so much that it was good to take these little breaks and then come back fresh. How has it been listening to it again for the reissue? So, this one, we didn’t know it was going to be our last one, but I look back on that record, and it was the last time the four of us were really all together, so it was hard for me to go back and listen to it after Dime got shot [Darrell was shot and killed along with three others in a mass shooting at the Alrosa Villa nightclub in Columbus, Ohio, on 8th December 2004]. I was on a tour bus about 2013, and we were sharing a bus with another band as we were on the same management, so they kept playing ‘Reinventing the Steel’ in the front lounge, and I’m always in the back lounge doing my thing. I’d walk in and grab a water or whatever, and I kept hearing this thing, and it just took me so long to listen to it, and finally, the last night those guys were on the bus, I finally sat down and listened to the whole thing, and it just blew me away! What did you think, listening back to it after all that time? I hadn’t listened to it in so fuckin’ long. When you get done with a record, you just move on; you’ve toured sixteen months on it, and the songs have taken on a different life unto themselves, but to go back and listen to the actual recordings; we just never did; we were onto something else. Going back and hearing that; god, that is such a fuckin’ heavy record, man. It’s so cohesive, and I’m glad that ‘Trendkill’ [‘The Great Southern Trendkill’. 1996] wasn’t the last one. It’s interesting that you mention going back and listening to your older material ahead of recording ‘Reinventing The Steel’, as I’ve always found opener ‘Hellbound’ to be reminiscent of ‘Cowboys From Hell’, in the way it kicks off, and in its’ sound. You know, you’re the first person to say that, but yeah, it has a similarity, because of the punchiness of it, and it’s also got the same time signature, and the same groove, so yeah! ‘Hellbound’, that was the one that when we played it live, we took fire [pyro] with us. Vinnie [Paul, drums] wanted to get a huge fire display, and we had these canons of fire that would shoot up fifty feet in the air, and you had so sit on your marker, and you had to know, during the song, where you were on stage, because if not, it would fuckin’ blow your goddamn lid off - meaning your hair - if you weren’t in the right place! God, what a trip! A lot has changed in twenty years, I’ll put it that way. Losing Vinnie [Vinnie Paul, drummer, passed away on 22nd June 2018] was fuckin’ hard. I wanted to go right back to Pantera’s early years, and the early albums, because you rarely see them talked about.

Dime was 15 when that first record came out [‘Metal Magic’, 1983]; I was 17. You know, we were just learning our craft. The thing that made it all possible, was his dad [Jerry Abbott] was an engineer at a studio. So, we would go making money at gigs, playing anywhere from proms to bar mitzvahs to roller skating rinks; just building a crowd up. That’s how we got our start. You’ve got to remember, when you start that young; I equate those old records to demo tapes that nobody… We just happened to press ‘em, then put them out and sell them at shows. And they were only on limited runs, so that history is completely different to when Philip got into the band. Once Philip got into the band, everything completely changed; we had a new sound. The look [glam rock image]? We were tired of wearing that same old bullshit; that kind of thing. There are still some gems in that early period; the track ‘I Am The Night’ has shredding as fierce as anything Dime ever played, for example. Yeah, but look, this is like going back and looking at your old high school notebooks and going; “look at how far you’ve come in between”. I don’t really like to talk about the old days because that was just us growing up and learning our craft. I will say this; a lot of bands didn’t have the opportunity at 17 years old to fuckin’ put a record out. We just happened to do it, and we paid for every fuckin’ lick of it; none of it was given to us. We paid for the studio time, we paid for the pressing of the record, and we never thought that that would go anywhere, nationally, globally, so it’s almost like, after the fact. But we really learned how to write a song and be a band. The old singer [Terry Glaze]? Shit, it was going nowhere, really quick. He just was not on the same wavelength as the three of us. The dude’s never had a job in his life. I see him shootin’ his mouth off in some of these magazines, and it’s like; “dude, you were in the band for fuckin’ four years”, you know what I’m saying? “Now you’re wanting claim to fame, 35 years later? Sorry, pal, you missed the boat!” So I don’t want to give any credit where it’s fuckin’ undue, you know? Once we got Philip in the band it developed into something else, and that was the Pantera that we know now, and that’s why we never talk about those old records. So, a daft question given what you’ve just said, but are those early albums ever likely to see a rerelease? Hey look, it’s great to go back memory lane, and all that kind of stuff, but those are the farthest things that I wake up for in the first of the morning. “Oh, remember that one tune ‘Nothing On (But The Radio)’, and the singer?” No! I mean, I hate fucking songs like that, but it was a growing process, and now, because the things are out, and they’ve been bootleged a hundred thousand times, people consider it a part of our history. It’s not. Unless Philip’s singing on it, it’s not Pantera. That’s the way I look at it. So you have absolutely no desire to ever see those reissued, officially? God no, god no! The brothers were against that, and I’m against it, and that’s just it. Period. It ain’t coming out. Moving on, what was it like when you first held a copy of the now iconic ‘Cowboys From Hell’ [1990] in your hands? It was amazing, the whole process. We had recorded that record three times. We demoed it, and then we came back and it just kept progressing and getting better, and; “here comes a new song”. Before we signed to a major label, we sold like 50,000 copies of that record [1988’s ‘Power Metal’] out of the back seat or our car through imports, and we were making really good money at $4 a record. If you come in with a major label, and they give you $100,000 to record the first record, and hardly anything to tour support, and then, when you get back home after 300 days, you’re in the hole [to the record company] for a million and a half dollars! Tell me about the cover artwork. When we shot the cover of this thing, we had this art director who said; “well, we’re going to put you in this background”. We never had an ‘art director’ in our fuckin’ lives before! We could never agree on a logo, let alone us getting in a room for the same picture; we didn’t give a fuck about any of that shit. So they took individual shots of us on a green screen, and then put us all in this old saloon picture, and I thought; “well, it’s got a vibe to it!”. We’re not thinking anything else creatively to put on this record, so let’s just put that out and see what happens. So they did a real cool package with the CD; it used to be called the long box, and I remember we opened up for Exodus and Suicidal Tendencies one night, and Kirk Hammett came to the show, and so he jumps into our RV, and he immediately was like; “hey man, here’s the news CD!”. We’d known Kirk and Lars and James and them for a long time, since like, ‘84, and Kirk just takes his nails, and rips the side of the box off, and goes; “fuck, yeah! I’m taking this to the car!”; he didn’t even stop. Pantera played a show in Belfast on the 1992 tour with Megadeth; that was a long way from Texas for you!

Oh yeah. The city was pretty fuckin’ heavy. Jesus Christ, I think we played the Ulster Hall, and it was bombed the week before, I want to say. I think we stayed in a hotel because we had to fly over, and then I guess we played two different shows in Ireland. Philip and I, we always were early for bus call, and I remember we came out, and I remember the turrets, and those little bitty tanks that they had, and those turrets just zeroing in on us as we were headed to the bus, and I was like; “holy shit. Fuck, man!” So much for going and grabbing a donut or a cup of coffee somewhere. We went straight to the bus. We had our suitcases with us and just got in there as quickly as we could. We had no fuckin’ idea, politically. I’m a history buff and I knew kind of what was going on in that city, but it was just; “let’s get to the show, everybody be really careful, don’t wander out anywhere, let’s all keep together”. That was the kind of band we were; we all took care of each other. Later on down the road, of course everybody went their own way because it went fuckin’ insane, but back in those days, it was our first time around the world, so playing that place was like; “let’s get in and do it”. That tour launched the band globally, and just a few years later in 1994, you reached number 1 on the Billboard 200 with ‘Far Beyond Driven’; how did that happen?! I’ll tell you what happened; it was us sitting outside that bus signing autographs until the wee hours of the morning when the sun was going up, and having a tour manager go out and buy beers at all hours of the night. Most bands would jump on the bus real quick and act like fuckin’ rock stars, but we were out there just hanging with the fans, because we were fans of the music ourselves. It turned us into a whole bunch of different bands that guys were into in different countries and stuff, and it was very cool, man. Of course, when the crowd got bigger we couldn't do that all the time. When ‘Far Beyond’ came out, we were headed out on a plane to somewhere, and I walked into one of those curio shops at the airport, and they had a USA Today sitting there, and it said; “Pantera Hits Number 1 on the Billboard Charts. The unknown band from Texas…” and they said something else, like it was flash in the pan; well, we’d just worked nine years of our fuckin’ lives to get exactly where we were at that point, so no, it wasn’t just a flash in the fuckin’ pan! How did you feel reaching that milestone of getting a number 1 album? It was a shocker. When you have that number 1 record, all of a sudden it puts you in this other plateau of; “well, we’re doing something right”. The way I always kind of look at it is, you always keep your expectations around [reaching number] 5, and if you go below that you need to pull your fuckin’ bootstraps up, right? And if they go above it, then you know you’re doing something good - keep doing what you’re doing! Now it’s at the point where you go; “okay, all this wear and tear”, and all the, you know; it’s a long way to the top, if you wanna rock and roll, you know, the AC/DC song? And that’s the fuckin’ truth. So, it was like we belonged now; we had arrived, even though we had done so much work before that. We did in-stores [signing sessions] all across America, in the Time Warner jet. We were doing about two in-stores of 2,500 - 3,000 people a day! You’d get back to the hotel and you’d go to sleep, and you had a 9 o’clock call to get in the Lear jet and go crank out again. We did that for three weeks before the record came out, and I think that had a lot to do with that [its’ success] too. The fans were obviously ready for it, right? That record sold 600,000 units out of the box, in the very first week. They shipped it platinum. It was fuckin’ insane, man! I mean, that’s when you jump off into the territory of; “oh shit; what comes now?” And here comes the money, and the fame, and all that shit, which none of us cared for - maybe Vinnie - but, once that money starts rollin’ and flying in, it’ll start to fuck with you, if you don’t have the right people to keep you grounded. All we had was each other. I mean, management was not doing shit; they just answered the phones. Pretty much everything that we did, we always kept that DIY - do it yourself - mentality during the entire time with what we did, but it was really cool, and I’ve got some really great stories I could sit and tell you all day long about that! Go on… By the time we reached New York, we were staying at this place called the Rhiga Royal, which is in Uptown, and we were in the elevator, and the fuckin’ Bee Gees were in the elevator. This was ‘94, and apparently, because there was such hype over these kids in this metal band coming out with a number 1 record that knocked out Bonnie Raitt, Ace of Base - those guys sold millions of records over in Europe - and they go; “you’ve got a number 1 record, we have to buy you a drink. Would you mind?” I think it was me and Dime, and I said; “I would be honoured to sit with the fuckin’ Bee Gees”, Dude?! Come on! I mean, some of the greatest songwriters ever, of any genre, of the last six decades. And I became really good friends with Barry [Gibb], and his son [Steve Gibb] who is about four years younger than I am. I took him on the road with Down, and he was a tech for all those years, and I’ve stayed at the family house. The Gibbs are really good friends. It must be hard to imagine how huge the band would be if you were able to tour, had all four members been alive today; surely Pantera would be bigger than ever?

It would be sold out stadium shows, yeah. Offers still come in for Philip and I to do it if we wanted to, but if you don’t have the other guys in the band it’s not going to sound the same. If we were ever to do something like that it would have to be spot on, or I wouldn’t do it. It would be a tribute. I wasn’t going to bore you with the usual question about a reunion with Zakk Wylde taking Dime’s place. It’s going to come up, and it wouldn’t be Zakk Wylde, I guarantee you that. I’ve just put it out there so we can get on past it. Moving on to ‘The Great Southern Trendkill’, and you hinted at the start of the interview that it isn’t one of your favourites. That’s just the way it goes sometimes. There was really no concentrated effort; we were just going through tracks, and there’s some great standouts on that fuckin’ record. ‘Floods’ is one of my favourites, probably because me and Dime wrote that thing on the spot, and recorded it on the spot. But it’s funny, man, in the overall picture, for me, that’s the least that I consider a favourite. For the fans, it’s like the fuckin’ ‘die to’ record, you know?! Is that because it was a difficult record to record? Phil recorded his vocals separately in New Orleans, for example. It made more sense. It was a lot easier for him to do that. He always came with the vocals after the point. He came down for some of the tracking and some of the riffs and all that kind of stuff, but it made more sense for him to be at home. He was comfortable. It wasn’t like the band was splitting up or any fuckin’ bullshit that the press gets a hold of; it was just an easy, simple, you know? He didn’t have to travel; that was the main point when Philip moved back to New Orleans. It wore on his fuckin’ ass, you know? The album kicks off in absolutely brutal fashion, with the title track. You know, I wasn’t on that. It was late night, I think Philip was down and it was a late night session, and there were some friends in town and they made this track into something. I don’t know, just because I wasn’t there. I could have added all kinds of shit to it, but I just left it the way it was. I wouldn’t say Vinnie was a [part of the] process of it - because they recorded it late at night. Dime always had all kinds of spare parts just sitting around, and it was a ‘Dime and Phil’ moment, so you didn’t want to step on that. Like, bringing me and Vinnie in and reworking the song, I think it would have taken away from it. And they had, we had a dear friend Ross Karpelman play keyboards on it - just this little shitty Casio, I think. It was more like a home demo, but it was cool. If you think about that riff and the time signature in it, it’s almost like an old Irish ditty, you know what I’m saying? Yeah, that was one of those obscure tracks. Bringing things back to ‘Reinventing the Steel’, and those final European dates you mentioned were meant to be the ‘Tattoo the Planet’ shows. You were in Dublin about to start the tour, and then 9/11 happened. Yeah, we weren’t even going to rehearse, we were just going to play the shows. When that happened, we had just flown out of New York the night before. We took a late flight and got into Dublin at some ungodly, 5 o’clock in the morning thing. It was just me and Philip and Vinnie, and we had our security team and tour manager, and Dime rode with the crew. The crew came in whenever they could get, because there was a ban. I think they were already in the air, like maybe two hours later. The three of us were doing press in New York, I believe. So we get to Dublin, and my tour manager just happens to have a bottle of fuckin' Crown [Royal Whisky] on him, and we devoured that, and about three hours later, I hear this phone, and it’s one of those big, loud, old-timey phones in the hotel, and I had two different rooms, so, one was the bedroom, and the other had couches around, had a TV sitting there, and he goes; “turn the TV on”, and he was screaming his ass off. About that time I saw the second plane go through the fucking building, and I completely just freaked the fuck out; we’re two blocks from the god damn United States embassy. How long were you there for? I didn’t leave that hotel for two weeks. It took us that long to get back home. The crew came in that morning, I met them downstairs, and I said; “we’ll put the blackline up, but don’t plug anything in”. And Philip and I made the decision then and there; “look, if this is happening, it could be happening anywhere. We don’t know what’s going on”. We had no intel except for fuckin' BBC propaganda that we’re seeing, and the strings were pulled really quickly on that one. Vinnie and Dime went out every fuckin’ night. We just stayed and watched the horror. It really scared the fuck out of us, and it was just one of those things where safety was the biggest precaution. We could have played the end of the tour, but you know, there’s still dead Americans on the fuckin’ ground, and I’m just not into that. That was, essentially, where the Pantera story ended. After that, at that point, man we were so burned, just fuckin’ burn out. Sixteen months we had been on the road or something crazy like that, and we were all just to a point, after twelve years of just non-stop touring; album, tour, album, tour; we needed to take a break, you know? After that, you ended up working with Phil Anselmo in Down.

The craziest thing is, Philip and I had this Down record [‘Down II: A Bustle in Your Hedgerow’, 2002] in the can since ‘98. When we had a little bit of a breather he called me down for a weekend and said; “do you want to jam on some ideas”, but he didn’t get specific, so I was like; “yeah, sure”. It was one of those invitations that was few and far between. You know, I was going down there all the time just to see the guys; Phil’s friends who he grew up with and all that kind of stuff. So anyway, I get to his house, put my suitcases down, and there’s fuckin’ the rest of the band; Jimmy Bower; Pepper Keenan who I’ve known for fuckin’ ever; Kirk Windstein, who is still a dear friend - all the dudes are. We had a couple of shots and beers and went downstairs, and wrote that whole record, pretty much. And at the time that we got back [from the aborted 2001 European run], Pepper called and said; “do you want to go make this record?” Relationships within Pantera started to go sour at that point. Everybody had their own time when we were all in different bands, right? So we just thought we’d put the record out, not tour or anything. We did the record in twenty seven days and we mixed it; Pepper and I, up to New York. It was just weird. We needed the break from the four of us. But it was one of those things, and it left some bad taste in the brothers’ mouths, you know, and it was not what the intention was at all. It was just fuckin’ another project. This is the one thing that I learned; I did the Jerry Cantrell record [‘Boggy Depot’, 1998], and when you go and jam with other guys, it makes you appreciate the band you’re in even more. And then you ended up caught in the middle of what transpired with the split. Some bad press, I was caught in the middle of fuckin’ all of it. They couldn’t get on the phone and call Phil himself; they had to call me to get in touch with Phil. I was like; “you know what? Fuck you all. When’s there going to be time for me? I’m tired of breaking up all these little fuckin’, sore butt sessions with you fellas”. I had just had it. I just, at that point said; “we all need to go into the padded cells, and fuckin’ get the fuck out”, you know what I’m saying? Before we wrap up, I wanted to quickly touch on the Rebel Meets Rebel album. That was a Dime little dandy. It was just one of the side things that we were fuckin’ around with. In 1999 they called me to see if I wanted to play bass on it, and I said; “yes”. Dime just loved working with Dave Allan Coe. It was just one of those things where it was his baby. We were all branching out to different things. We just needed to take a break from each other. Finally, what’s next for you? Oh Jesus, that’s a whole other chapter, man! You have to catch me on another day for that! What I’m doing now, it’s insane, man. Yeah, we’ll have to talk about that another time! But that’s where I’m headed, I’m telling you that. You’ll hear the new one, June. Like this interview? Like us on FaceBook and follow us on Twitter for regular updates & more of the same. Pantera's 'Reinventing the Steel 20th Anniversary Edition' is out now via Rhino Records. Get it here. |

|

Pantera.

"It’s a long way to the top, if you wanna rock and roll, you know, the AC/DC song? And that’s the fuckin’ truth". - Rex Brown

© 2016 - 2024 eonmusic.co.ukContact: [email protected]

|