|

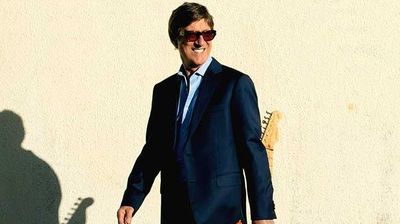

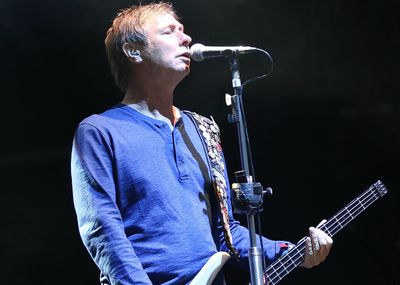

For a certain generation, Nik Kershaw defines an era. One of the most identifiable acts of the 1980s, the Bristol-born singer was ubiquitous in the middle of the decade, releasing a brace of multi-platinum albums, scoring five UK Top 10 singles, and playing at Live Aid in London. Going on to become a successful behind the scenes songwriter, Nik is now back to writing, recording and touring. With a series of ‘An Evening With’ gigs announced for towards the end of the year, we sat down with Nik for a chat about all of the above. Human racing; Eamon O’Neill.

Hi Nik, how are you today?

I’m good actually, I’m pretty good. Yeah, I can’t complain. You’re in the studio today, aren’t you? Yes; it’s laughingly called a ‘studio’. It’s just basically a barn on the end of a bunch of other barns in the middle of nowhere that I can make loads of noise in, and it’s got gear in it and computers. It’s not really a studio; I mean, I can record most things in here, but I can’t do a lot of live work, like drums and stuff like that. It’s a ‘production studio’, shall we call it that? So you’re actually at work on some new material right now? I was up until a couple of weeks ago, but I’m starting to panic about some acoustic shows I’m doing in the autumn. So I’m knuckling down to sort out what I’m actually going to be doing on those shows, and sorting out the video that I’m going to need to run with it and all that kind of stuff. I was in the process of recording tunes for my new album, but that’s gone on the back burner for a couple of months. You’re talking about your upcoming ‘An Evening With' shows. Yeah. It’ll be along the lines of what I did a couple of years ago, so it’s just basically me on stage with a guitar and a microphone and a few video screens, talking nonsense and playing a few tunes, really. I can’t build it up any more than that! Last time, I took questions from the audience and stuff like that. Maybe I’ll do that this time, but I haven’t quite made up my mind; it back-fired a couple of times last time! What is it that you like about playing live in that format? You build a completely different relationship with the songs, really, because all of a sudden you have to strip them down, and you’ve got you and a plank of wood and a microphone, and that’s all you’ve got. So it’s great to do that, but it’s also the fact that you are right in the thick of it amongst the audience as well. It’s very rewarding. That intimacy is the polar opposite of when you appeared at Live Aid in 1985; what was it like stepping out onto that stage that day? Well, it wasn’t intimate, you’re right there! I can’t explain the terror, really. It was one of the most terrifying things I’ve ever done. Everybody was in the same boat; nobody got a sound check, nobody got any kind of a run through or anything, so basically you were just walking on stage in the hope that somehow your equipment; a) would be there, and b) would be working. When you started playing those first chords, did a sense of relief wash over you?

I can’t remember which song I started with, but I actually did forget the words in ‘Wouldn’t It Be Good’. That was one of those out of body experiences I will never forget; me looking at myself, telling myself that I didn’t know the words to the end of the verse I was singing, and the ten seconds that elapsed between that point, and me getting to that point in the verse, where I was frantically singing and trying to remember the words to the next bit at the same time, and failing. I ended up singing the first verse again. It was a moment I’ll never forget. Have you watched the performance back since? It took me… when was the DVD released? It would have been 2005, so when that came out, I braved it. I looked at that bit where I forgot the words, and you’re right, it wasn’t even half as bad as I remember it. What was the vibe like backstage at Live Aid? There were all these legends wandering around. Apart from not wanting to make a prat of yourself in front of a TV audience of two billion, and eighty thousand people in the stadium, you really didn’t want to look stupid in front of all your peers and your heroes. I remember just before I went on chatting with Sting in the backstage area, because he’d just released his first solo album ‘The Dream Of The Blue Turtles’, and I just remember having a chat with him about recording it in Barbados or whatever. I can’t believe I could even get it together to string a sentence together to be honest, before going on. What did you do after you came off stage? After I came off, I watched Bowie from the royal box, and Queen, because that was where the hang out area was if you wanted to watch anything. The general atmosphere there, it was weird because you were aware of why you where there and what the whole purpose of the thing was, but also, it was quite celebratory as well. It seems like those things don’t really go together, but they kind of did, because this thing was totally thrown together at the last minute by Bob [Geldof], and it was actually happening, and you were there. Money was coming in, and it was a great, great atmosphere. Do you still have the guitar that you played at Live Aid? I don’t, no. I don’t know what happened to it. It was built by a fired of mine, a guy called Dave Gladden who used to make all my guitars. I’m trying to cast my mind back to every time I’ve moved house in the last twenty / thirty years, and what could have happened to it. I know I haven’t got it because I’m standing here looking at all my guitars right now, and I know it’s not in amongst them. I think I might have given it back to Dave at one point to do something with, I just haven’t got a clue. You’ve got quite an unusual style as a lead guitar player; how did you come up with those harmonies in the solo to ‘Wouldn’t It Be Good’?

I’d been playing in fusion bands before, and guitar was what I learned my trade on. But when it comes to solos and stuff, I’m not the most spontaneous guy on the block. If I just sit down and play over a few chords, it sounds pretty much like everybody else. I’ve got the same licks as everybody else, pretty much, and it doesn’t satisfy me as someone listening to the record. So what I usually end up doing is just looping the track and just singing different bits over it and then sticking it together and then learning how to play them. I still do that. Obviously if I’m singing it, it’s a direct line from my brain to my mouth, and it’s just ‘bang!’ there it is. Steve Vai used a similar technique when he was writing ‘For The Love Of God’, and he said that it takes away from what your fingers expect you to do. Yeah, exactly. Most guitarists have their little shapes that they see, and they use them all the time on the fret board, and it’s obvious to just go in ‘there’. Also, the other thing is it makes your fingers go somewhere else, so all of a sudden your fingers start learning different patterns through that process, so it’s good for the guitar playing as well. Did you build those harmonies yourself too? Yeah, again, it’s either singing them, or just working them out, just knowing what those harmonies should be. There’s an incredibly rich production on those introductory chords on ‘Wouldn’t It Be Good’. Peter Collins was the producer of the two albums [‘Human Racing’ and ‘The Riddle’, both released in 1984], but all we actually did for most of the tracks, was pretty much just re-record my demos. The exception was ‘Wouldn’t It Be Good’, because there was no demo as it was one of the last tracks that I wrote at the time. But I knew the chords that I wanted, and I mapped them out on a keyboard. I tried playing the chords with a kind of aggressive guitar sound, but because there was a clash in the way the harmonics went together, it just really sounded quite unpleasant. But I was not averse to listening to the odd Queen record, and I suggested to Peter that we make a kind of guitar orchestra, like Brian May would do, just to separate those notes so you don’t have the harmonics clashing with each other. So those chords are actually made up of single notes layered? I think I’m playing fifths in one go. But some of the more subtle notes just didn’t work, so I think I did about four takes of each note, so there were a lot of takes, and this was all on analogue tape, obviously. We then bounced them all together to make that one sound. I very rarely get asked about the technical side of it, and it’s one thing that really interests me. I mean, I love the whole recording process and why things sound like they do. I’m fascinated listening to other people talk about how they make records. I have to ask about the video for ‘Wouldn’t It Be Good’; I believe making it was an uncomfortable process.

It was. You know what, out of all the videos I made, I only once got to go somewhere nice and sunny, and that was for Don Quixote; we went to Spain to film that. With this particular video, most of it was filmed in a disused block of housing which was being refurbed just across the road from Buckingham Palace. It was January, and it was freezing cold because there was no heating in this property at all. What I was wearing was basically a calico suit with reflective tape – something called Scotchlite tape stuck all over it, which obviously needed repairs, pretty much after every take. So it wasn’t the most comfortable piece of clothing I’ve ever worn, and it was the best part of three days shooting. It sounds very trying. Videos never were that comfortable. I don’t think people appreciate how much bloody hard work they were, or still are! It’s a really long process. When someone says; “We can cut this down to a day’s shoot” - they mean a day; they mean 24 hours. You come out of it absolutely, totally exhausted. During that peak period on 1984 – 1985, was it like a rocket taking off for you? It was totally a rocket ship, yeah, or a high speed train, in that you couldn’t get off. It’s weird because it was everything that I’d dreamt about happening, and all my dreams came true very quickly. So there was that part of me going; “Wow, this is amazing”, and there was another part of me going; “Wow, this is terrifying!”, and there was another part going; “This is totally exhausting”. It just didn’t stop for about two and a half years, and from that first hit onward, my life wasn’t really my own. I was at the mercy of record company schedules, promotion schedules, marketing schedules; I was just a part of that process, really. Why do you think success in America eluded you? That’s the one country in the world that really didn’t happen for me. MCA were an R’n’B label in the States, so we went over there with ‘The Riddle’ and silly reflective suits and god knows what else, and they just didn’t really know what to make of it. It was quite ‘English’ what we were doing, so they just didn’t have a handle on it. ‘Wouldn’t It Be Good’ got close, it was flying up the charts at one point and got a ‘bullet’ - which apparently is good. I did some great gigs over there. I supported Paul Young and it all looked like it was happening, but I just never sold any records, it just never kicked into sales. Did you make the decision to step away from the limelight? I won’t pretend I wasn’t half pushed; I kind of was. I had a four album deal with MCA, and they didn’t ask for a fifth. This was 1989, and I’d just come off tour supporting Elton John, and I was pretty exhausted. We were just about to start a family, and I thought; “Do you know what? I’ve had enough of this”. I could still make music and write for other people, so I did that. I did that until 1998 before I started making my own records again. Your biggest success as a songwriter came when you penned ‘The One And Only’ for Chesney Hawkes; were you ever tempted to keep it for yourself? No, I wasn’t; it was never an option. It was pretty much the first song out of the bag when I decided I wasn’t going to make records anymore, and I don’t remember thinking; “Oh wow, this is going to be great, a massive hit; maybe I should record it?” I just stuck it on the shelf, and it wasn’t until I think a couple of years later when Ches’ dad walked into Warner Chapel music and they played it to him that anybody noticed it. There’s various reasons why songs are hits; it’s not just the song. I could have recorded it, but my time probably had come and gone by that time, so I wouldn’t have got the promotional opportunities and everything that a new artist like Chesney had. I think that was one of the reasons it was a massive hit; because Chesney was a new face and there was a movie that went with it, and loads of reasons why people engaged with that song. Finally, I should tell you that you’re in a very exclusive club along with my late grandmother, as one of only two people I’ve ever heard use the word ‘scullery’. *Laughing* My Nan had a scullery as well. She had a big old house up near Great Yarmouth that we used to go to when I was a kid. The coldest house I’ve ever been in, it was. But yeah, she had a kitchen, and on the back of the kitchen was a scullery. It’s where we had breakfast and it’s where my Grandad used to sit in his rocking chair in front of the fire. Is that what the lyric ‘nights in the scullery’ from ‘The Riddle’ referred to? I can’t claim that any word in that song refers to any particular real event or persons living or dead. I don’t know; it’s just a word that was in my vocabulary and it was probably there because of my Nan. I think the biggest reason I used that word is because it rhymes with ‘me’! Like this interview? Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter for regular updates & more of the same! Nik Kershaw plays Dublin's Vicar Street on 9th October 2017. A full list of dates can be viewed below. For ticketing and further information visit NikKershaw.net. Nik Kershaw 'An Evening With' 2017 Dates: 8 Sep - Norden Farm Centre, Maidenhead 10 Sep - The Lowry, Salford 12 Sep - Union Chapel, London 14 Sep - Hertford Theatre, Hertford 16 Sep - The Atkinson, Southport 17 Sep - The Sage, Gateshead 20 Sep - The Apex, Bury St. Edmunds 21 Sep - The Stables, Milton Keynes 23 Sep - Theatre Royal, Winchester 24 Sep - The Robin 2, Bilston 28 Sep - Floral Pavilion, New Brighton 29 Sep - The Capitol, Horsham 30 Sep - Assembly Hall, Worthing 9 Oct - Vicar Street, Dublin. |

|

Nik Kershaw

"Live Aid was one of the most terrifying things I’ve ever done. That was one of those out of body experiences I will never forget; me looking at myself, telling myself that I didn’t know the words."

© 2016 - 2024 eonmusic.co.ukContact: [email protected]

|