|

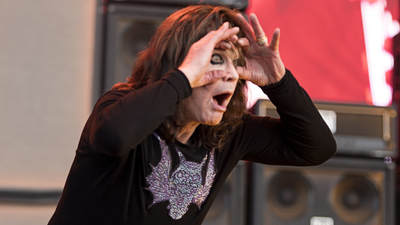

Michael Beinhorn has worked with some of the biggest names in Rock. The man behind the desk for Red Hot Chili Peppers, Marilyn Manson , Korn and a whole lot more, he’s perhaps best-known as the producer behind Soundgarden’s monolithic ‘Superunknown’ album. Launching a new pre-production service, we sat down with Michael to talk about the importance of song writing, his work with Ozzy Osbourne, and the album that brought the world ‘Black Hole Sun’. On the other side; Eamon O’Neill.

Hi Michael, you’re starting a new venture offering pre-production to musicians and bands; why have you decided to focus on that area?

Well, the focus is on pre-production, and I discovered over this past fifteen years now, that fewer and fewer people are actually using pre-production to make records. A lot of people because of budgetary restraints are just rushing into recording studios with a bunch of songs once they’ve written them, and they don’t really think about what may or may not be working with the songs. That decision is one of the single most vitally important that a person can make before they’re going to make a recording. If they’re going to rush into the studio with a bunch of songs that are potentially good before they’ve honed the arrangement right, they’re going to regret that. It’s really about focusing, and putting as much attention as possible into the end result. For artists who arrive into the studio without doing any pre-production, would you say that it ends up costing them more in studio time? Yeah. The thing is there’s one finite aspect of recording right now, and that’s the budget. The budget now is what dictates everything. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing, because it’s important to have some kind of limitations when you’re making a record, depending on what level artist you are. The thing is that when every single decision is dictated by how much or how little money you have to make your recording, it kind of puts you up against a lot of unfair pressure. For example, if you’re work is based in creativity, it doesn’t make sense that you should be completely and utterly restricted by how much money you have to work with. I mean, sure, you’ve got money to make a recording on the one hand, but on the other hand, there still has to be considerations made; how are we going to make this the best recording possible? Surely that’s the most important question? That is the question that’s always been asked when I’ve been involved in recordings in the past, regardless of what the budget was. There’s no reason in the world why artists shouldn’t be able to deal with the same kind of variables, no matter what their financial situation is. That’s really where this comes from; I want to make available to people something I consider that has been vitally important in the making of records for decades. To a lot of extent, it’s made a lot of recordings that people are familiar with, as good as they are; because people had time to work on them, they had time to invest in creating the structural element, not just going in and banging a bunch of parts out. With the advent of quality home recording in the last decade and a half, has the role of the producer become more undervalued? It depends on the genre of music you’re talking about. It also depends who the artist is. In many cases, the role of the producer has actually expanded considerably, and I don’t necessarily think that that’s the best thing either. I’ve always enjoyed a healthy balance between the producer and the artist, really. We have a collaborative aspect going on in a recording; with an understanding that the artist is really the person who’s responsible for creating the music, and the producer is there as someone who’s there to help recognise the vision. That’s strength in numbers. You have a bunch of talented people coming together under one banner, with a joint vision. Assuming that everybody’s wonderfully talented and there’s great material for it, and great performers, the resulting collaboration is always fantastic. That magical collaboration you’re talking about is exemplified perfectly on Soundgargen’s ‘Superunknown’, which you produced in 1994. Yeah. I will say that once the songs were written, I didn’t really have to do a whole lot, in terms of rearranging it. I think it was more a matter of getting them on the right track with their stuff and really encouraging them. But, if I hadn’t been there, the record wouldn’t resemble by a long shot what it looks like now, because the songs that they initially started with were like a shadow of what the record wound up being. What was it that you brought, was it arrangements, guitar sounds – the picked verses of ‘Black Hole Sun’ for example?

As far as the Leslie guitar that he plays on the arpeggios – which I think is what you’re thinking about – that was all in the demo. That was his demo, but to give you an idea of what my involvement was from, I was getting a lot of demos from Chris [Cornell]. As I mentioned, they started with a bunch of songs, some of which were good. About four or five actually wound up being on the record, but the rest of it was kind of meandering jams, and it wasn’t anything steady, and none of the songs that were singles were in those batch of songs. I’d say the most important aspect of it was, I said to them; “Look, we can’t get started here, you don’t have a record. We need to write more”. So you sent them away to write? I was getting songs from Chris, and after about a month and a half, I realised that he was starting to go in a natural direction. He and I had a conversation about it, and we focused on what he really loved musically, which is something that he hadn’t really considered. He was trying to write songs for Soundgarden fans, which I strongly urged him against, because my feeling is like; “look, if you write the song, and your band plays it, it’s going to sound like Soundgarden!” You don’t have to write songs that are going to please the constituency of your fans; they’re either going to stay fans or they won’t - all you have to do is write songs that you really love. It sounds like that piece of advice changed the direction of ‘Superunknown’ considerably. About two weeks after that conversation he sent me a cassette tape and I played it. There were four songs on it. The first was ‘Fell on Black Days’, the last was ‘Black Hole Sun’, and from the first few notes of ‘Black Hole Sun’, I was like; “Oh my god! This is incredible” I listened to the song many, many times - I just kept playing it over and over and over again, and I just called him up, and I was like; “This is incredible. We’re ready to record now. You’ve basically got the most important track on the whole record, and it’s one of the best songs I’ve ever heard”. The song has gone on to become almost immortal; Is it strange to think you were one of the first people to ever hear it, and have a hand in its creation? It’s still pretty mind blowing. It’s wonderful because people still listen to it, it’s wonderful that people are still inspired by it and still love that record so much, and it’s wonderful because the record does what I wanted it to do. I meant to do something that would hit people emotionally, that would affect them; that they wouldn’t just hear it, but they would feel it, that it would be something that would get under their skin, and would stay with them. And that’s not like; “Oh, I wanted to sell millions of copies”, that’s like, yeah, that’s great, I’m very happy about that too, but it’s secondary. It was really important to me that this album would mean something to people. I knew that this band could create something, I just had no idea it was going to be that. And that people would be asking you about it all the bloody time! If I told you I’m sick of talking about it; that would be disrespectful, and it would be terrible, because that song was beneficial to all of us. And it’s a wonderful, wonderful piece of music; even dissecting it musically is so much fun because there’s so many wonderful facets to it that I think very few rock songs actually have. Moving on, and in 1995 you worked on Ozzy Osbourne’s ‘Ozzmosis’ album; was it a struggle to get that one down?

It took a long time [*laughing*]. It took a long time trying out some of the material for it, and I also worked Ozzy’s record in the middle of someone else’s record. It took months to assemble all the material for it and to coordinate everything. It was definitely a movie, and I remember we were looking at studios and Ozzy called up and he told me all the studios he didn’t want to work in, and then he hung the phone up! [*laughing*]. We wound up tracking the record in a studio in Paris, and it was a long, drawn out process. You had Ozzy, Zakk Wylde, Geezer Butler and Rick Wakeman on there; does it go to show that even with the right ingredients, it doesn’t necessarily lead to a great album? It’s funny because you can work as hard as you can, and you can put as much intent and as much effort into something as you possibly can, but if the stars aren’t aligning and everyone isn’t on the same page? You really need to have so many things heading in the same direction in order for something like that to work. I’m certainly very grateful that the record was a [commercial] success. Unfortunately a lot got lost in translation too. I’d recorded it a certain way; I had come up with this two inch eight track analogue recording system that no one had ever used before, and I tracked the drums on it, and unfortunately when it was mixed, the guy who was mixing it didn’t really know how to work with it. He lost all the subtleties and the depth of the drum kit, so that part of it was kind of heart breaking. It sounds like it was a completely different recording experience to ‘Superunknown’ the year before. Well, it’s hard to describe it exactly. Comparatively speaking, on a record like ‘Superunkown’, there was just an energy about it, like, I can’t really describe it. It was one of these things where you just knew that this thing was going to happen no matter what; like we were all just pawns it in. I could say; “Oh, I did this, I did that”, but the fact is that we were really just being drawn along by some other kind of force or energy or whatever, that took the whole project to its inevitable conclusion. To me, that’s the best that you could hope for when you have a recording project. Ozzy’s record? Not so much. He’s not much of a participant, or at least he wasn’t on that record. He kind of left us to our own devices. It was me and the other musicians, and I think when you’ve got a record that is basically by a solo artist, it’s a little more difficult if the solo artist isn’t really heavily involved in the creative process. Despite that, it still contains ‘I Just Want You’, which is still a classic, underrated track. It’s really funny, I only had one DAT recording of the way the drums sounded when we first tracked them in Paris, and to this day – this is going to sound very immodest, and I apologise for that – but I’ve never heard a better recording of drums in my entire life. I mean, it was that good. For you, what would you point to as examples of some of the best produced albums recorded?

Oh, there’s so many, oh my god. It really depends. The thing is production is something that you can’t always detect what it is, because it’s so much more. The only way you could really know what production really is, is by comparing an album that an artist did with one producer, with one they did with another producer, and looking at where song structures were changed, as well as sonic elements. From an overall perspective, obviously Beatles records are incredible, as are Led Zeppelin records which are self-produced; that’s a feat in itself, because there’s virtually no one else on the face of the earth - save maybe Prince, who could really self-produce like that. That’s over the top. Chris Thomas[The Sex Pistols, Roxy Music, U2]; his records are amazing; and I think no matter what anyone says about him, I think Mutt Lange is a genius. His records with Def Leppard and AC/DC are stupendous. AC/DC is a great example of what you’re talking about; comparing the difference between the Lange-produced ‘Back in Black’, and the self-produced ‘Flick of the Switch’. Yes, and you can see where that went; you can see what Mutt actually brought to them. There’s an element that’s actually very subtle that Mutt introduced into their records. There’s a very refined quality to their records, and I think that that comes through in the sonics, as well as the feel of the performances. He’s a bass player, and he’s got a very, very refined sense of feel. I love what he did with their stuff. To me, adding contrasting elements, adding refinement to something that’s really rough and basic and nasty; that’s fantastic, and it gives the listener something to grab hold of. Moving back to your latest venture, what are you hoping to achieve? I would really like to focus musicians on making better recordings, and how they can be proactive in their own work. One of the reasons why recording projects still cost a certain amount of money is you hire some guy who takes a large portion of your budget, who’s going to go into a studio with you for a week, maybe two weeks, cut everything and then go. And that’s the end of your project, instead of taking time to really look at the songs and making sure that when you go in with that guy, your material is stuff that you’re so confident about, you have no problem laying it down. I spoke to someone recently who I’m working on one of these projects who said; “Before, the only way whether my songs were good, was once my record was completed and mixed”; now think about that, that’s kind of sad, being an artist but not knowing. That’s terrible, and I don’t see any reason why people should have to suffer through that, so that’s my aim. Does that mean that you’re no longer active as a producer, or will you be doing both in tandem? I’m doing everything! I don’t rule anything out. Like this interview? Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter for regular updates & more of the same. To enquire about Michael Beinhorn’s services, visit MichealBeinhorn.com |

|

Michael Beinhorn

"The producer is someone who’s there to help recognise the vision. Assuming that there’s great material and great performers, the resulting collaboration is always fantastic."

© 2016 - 2024 eonmusic.co.ukContact: [email protected]

|