|

Formed almost 50 years ago, the original Barclay James Harvest were true progressive rock originators. As well as achieving massive success in Europe with their defining 1970’s output, the band helped name the record label the would become home to the likes of Pink Folyd, Deep Purple and Kate Bush. Now split into two factions, singer John Lees' incarnation of the group are about to hit the U.K. for a series of dates in support of their ‘North' album. We spoke to John about the band’s history, longevity, and future. Child of the universe; Eamon O’Neill

Hi John, how are you today?

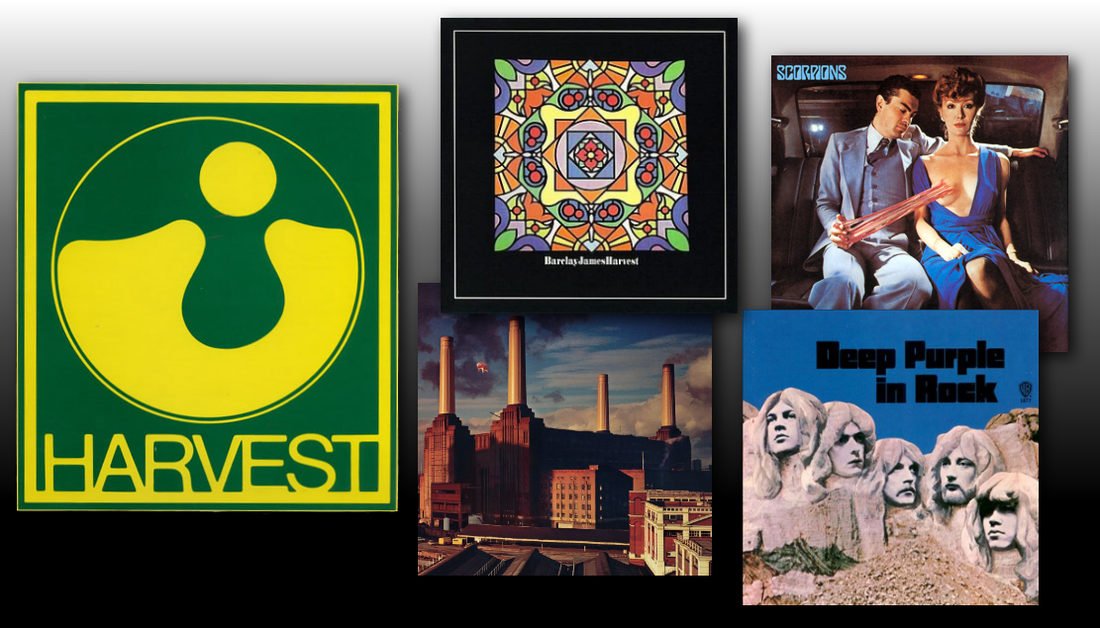

I’m fine. I’ve just got back from three weeks in Spain, actually, and we’re just about to go to Helsinki and Copenhagen in the next couple of weeks, and then we’ve got these dates in England, and then we’re off to Germany, France, Switzerland before Christmas. I think by the end of the year we’ll have done something like thirty concerts. Do you still get excited gearing up for a tour? No, because I’ve been doing it a long time! You don’t really get a chance to get that feeling anymore, but it’s really enjoyable because there’s no pressure on anything we’re doing. This run marks 50 years since the formation of the band. That must be a bit mind blowing even for you? I don’t think of it – I try not to think of it, anyway! It’s a totally different game now. I mean, you can tour really easily these days. When we were doing these enormous tours, before you’ve even started it you’re into the bank for hundreds of thousands of pounds; you had six articulated trucks ,and a couple of coaches travelling over Europe; you had to pray that nothing happened before the last two weeks of gigs, because it wasn’t until then that you actually paid for everything, so your profit was in those last two weeks. The pressure must be a lot less now. Absolutely, yes. I mean, we released a new album last year called ‘North’, which was a newly produced album, and it was really easy to do. At some point in my musical career, I had the option to build a studio and equip it, and it’s paid off dividends in the long run, because it’s where we rehearse, and also we can record there as well, so there are no recording costs for us. What do you remember about signing to Parlophone in 1968? It was fantastic really, but we’d actually done, initially, auditions for Decca [Records], and before they made a decision, we then did an audition for EMI, and EMI signed us. It was great, but we lost the tracks we recorded for Decca; our early songs - we couldn’t get them back. But the highlight was hearing our single the first time on radio, and it was played by John Peel. I remember thinking that it was absolutely fantastic, that. Signing to the home of The Beatles must have been a big thing for you. Yeah, and we were given the producer who’d done work with The Beatles as well, so that was quite interesting. We also recorded at Abbey Road, because that was EMI’s studio. We were kind of poor cousins, so we had to wait until The Beatles, and Cilla Black, and Cliff Richard and people like this had finished recording, and then we went in after them, which was mainly at night. You started your career at Parlophone but then moved to the Harvest label. We done the thing with Parlophone, and then there was this great debate where EMI wanted a specific label for what they deemed progressive music, or different music; classic rock or whatever it was at the time, and that became the Harvest label. The band has a strong connection with the Harvest Label in name too. Yeah, and I think we were the second album out on Harvest. We should have been the first, as it was kind of our instigation that gave the label its name. I think the guy was called Malcolm Jones, the head or A&R, and they were looking for names for the new progressive label, and we suggested ‘Harvest’. It went down on a list with other titles that were being considered, and then at the end it finished up that it was ‘Harvest’. Some of Barclay James Harvest’s most celebrated works have been recently rereleased; did you have much input into the deluxe editions?

Yes, all the remixes were done at our studio, which is where we work and where we record, and they were remastered by Craig [Fletcher] who plays bass for us. What was it like looking back over those albums? It was really interesting, because in those days you didn’t clean up the tapes – you left all the [pre and post-performance] talking on there, and all the stuff just stayed on the multi-tracks. So hearing yourself, and all the things you said while recording songs – some amusing; mostly amusing – was quite interesting, really. Actually, we’re going to do outtakes of all the conversational stuff, and that’s for the real die hard fans. 1977’s ‘Gone To Earth’ was your most successful album, selling over a million copies. Do those sort of statistics amaze you? Yeah, I mean, I don’t know how many albums we’ve sold all together worldwide, but there’s quite a few million, and it’s a terrific achievement because there was never a single from that album. All the success, really, was without a hit single. We’ve always had hit albums, and it’s quite staggering, really when you think about it. A popular tune in England is ‘Mocking Bird’, because it was one of the very first, early things we did, but I mean, we’ve never had a hit single in England, at all. The band has always been more popular on the continent, hasn’t it?

We were just lucky. We were touring big style in Germany when punk hit, and I don’t think the Germans liked that new wave, punk sort of stuff – I don’t think they took to it in a big way. So that whole time that that was going on, we were in Europe because we chose to go that way. We were touring back in England, and there weren’t the big venues then, and we’d got a big show, and we were breaking even, sometimes not even doing that, on sell-out shows. So, to find a way out of the situation, we went to Europe to try and break ourselves out there, and fortunately for us, that did happen. Then that kind of excluded us a bit from coming back to England on a regular basis, because the venues were bigger, so the show got scaled up even more and became even less viable in England. It was a good thing, but a bad thing. And that persists to this day, where the band are still a huge draw in Europe, but less so at home. Yeah, I mean, I’m looking here, and we’ve done quite a lot of work in Germany this year, Switzerland, France, all those countries. It’s very much a European thing, and then we come here and it’s still there, but not the same size of venues, which is nice really. It’s nice to play in that smaller environment where it’s much more intimate and it’s nicer to get the music across. Going back to the remasters, and was listening back tinged with a little melancholy, given that two of the band members have now passed away? Yeah, it’s good in a way, because it kind of keeps them alive. You know, when you listen and you hear those voices again, and it brings you right back to when you were doing them, so it’s a positive, rather than a negative. Of course, with Mel [Pritchard, drummer, who died of a heart attack in early 2004], it wasn’t a shock because I knew what his lifestyle was, and the way he was. But obviously with Wolly [Stuart Wolstenholme, multi-instrumentalist who took his own life in December 2010] it was just completely out of the blue, in the middle of work that we were doing together. It’s something you’ll never goer over. You played at Glastonbury earlier this year. Was this your first time, or did you play there before in the band’s early days?

No, that was the first time. It’s kind of a funny one; I didn’t want to do it. I was really not interested in doing it. I’ve done loads of festivals over the years, and they all tend to be the same. I just wasn’t interested, but unfortunately the group is a democracy, and all the other guys had it on their bucket list to do, so we had to do it. Would I do it again? No! So you didn’t particularly enjoy the festival experience? It’s great to play the music in that environment, but the whole lead up to it; I mean, we were headlining the acoustic stage on the Friday night, and it was just a sea of mud everywhere. The place is absolutely huge; there are people moving and wandering through from place to place all the time, and there’s a core of fans that are lucky enough to have bought a ticket – because you don’t know who’s going to be on when you buy the tickets. So the show was good, it’s just the run up to it; you’ve no sound check, you’ve no stage, so it’s not really a true representation of what the show is about. What can fans expect from the upcoming U.K. shows? A real cross section. We do our own support [slot], so we do about forty minutes where we play some older numbers; some of the classic ones like ‘Child Of The Universe’ and ‘Galadriel’, and ‘In My Life’, would you believe, which is a real oldie-oldie, and we finish that with a track off ‘North’ called ‘On Leave’, which we wrote to kind of explain how we felt about Wooly’s suicide. And then there’s an interval, and then we do the bulk of the act, which again is new stuff, there’s classic stuff, there’s a little segue in the centre which is acoustic. There’s a song in there called ‘In Memory Of the Martyrs’, which was written for the Berlin gig where we played on the steps of the Reichstag where we played to 180,000 people. So, it’s a fair whack of numbers. We never tent to retire numbers, we keep them up and running, so there’s a few on the reserve list that, depending on how we feel, some of those numbers go in as well. I think we play a number from about thirteen albums! There are now two factions of the original group – is a reunification out of the question? I really don’t think it will ever happen. Musical differences are the biggest part of this thing really – that’s why the band split in the first place. That’s why we’re keen to inform people that it is John Lees’ slant on Barclay James Harvest, which means you’re going to get songs written, extensively by me, unless from the original partnership when it was credited to four people. I think the same with Les [Holroyd], and his reincarnation of BJH; you’ll get all his material, and I think he plays a couple of my songs, but I’m not certain. But I can guarantee that when you come to see me you will not hear any of Les’ songs. Finally, I have to ask – where did the Barclay James Harvest name originate? It’s a complete abstract. We literally, between the four of us, we just couldn’t decide on anything, so we wrote words and threw then in a hat, and the last three pieces of paper left in the hat, we just said; “this is crazy, we’re going to be here all night, so whatever’s on those three pieces of paper, we’re having”. And it didn’t necessarily come out in that order, but ‘barclay’, ‘James’, and ‘harvest’ were the last three words in the hat. That’s what we called ourselves, and it stayed. Like this interview? Like us on FaceBook and follow us on Twitter for regular updates & more of the same. John Lees' Barclay James Harvest U.K. tour kicks off on Canterbury on 3rd November. For tickets, click on the links below. John Lees' Barclay James Harvest 2016 U.K. Tour Dates: 3 Nov - Canterbury, Westgate Hall. 5 Nov- Farncombe, Godalming, St. John’s Church. 9 Nov - New Brighton, Wirral, Floral Pavilion. 10 Nov - Norwich, St Andrews Hall. 11 Nov - London, Cadogan Hall. 12 Nov - Ipswich, Regent Theatre. |

|

Barclay James Harvest

"We were kind of poor cousins; we had to wait until The Beatles, and Cilla Black, and Cliff Richard and people like this had finished recording, and then we went in after them." - John Lees.

© 2016 - 2024 eonmusic.co.ukContact: [email protected]

|